VISIT THE VIRTUAL GALLERY EXHIBTION HERE

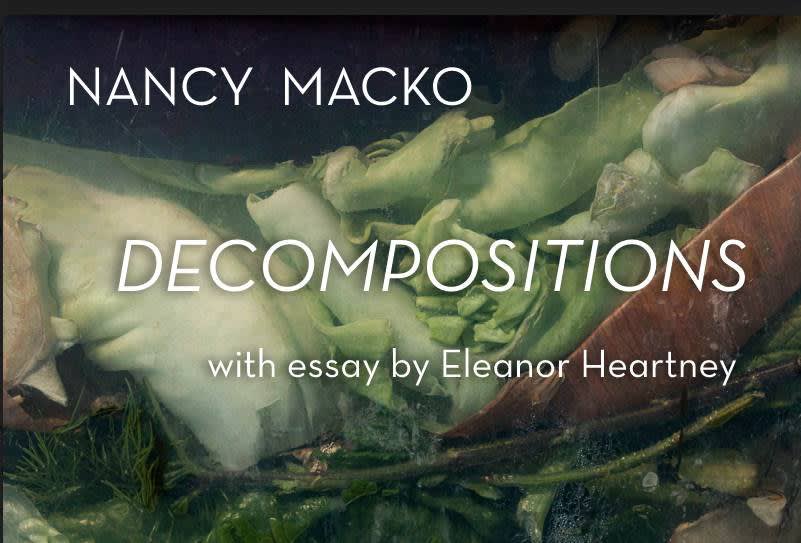

The photographs in Nancy Macko's Decompositions series present amorphous forms

floating in a watery ether.

Light streaks through the compositions, muted slightly by a translucent film that gives the whole composition the soft patina of an old master painting.

The images hover between abstraction and representation.

Recognizable scraps of organic waste - a striated piece of onion skin, a curl of orange rind, the softly undulating rumple of a cabbage leaf - come together to suggest mysterious landscapes, human bodies, strange sea creatures and soft folds of fabric.

The double readings bring to mind the Renaissance portraits of painter Guiseppe

Archimboldo. His meticulous trompe l'oeil renderings of collections of fruits and

vegetables (as well as fish, birds, jugs and books) combine to form delightfully odd

caricatures of the real and invented notables of his day. But while individual fruits

and vegetables in Archimboldo's paintings tend to be ripe and succulent, Macko's

are, as the title of the series suggests, in a state of decomposition. This is not

surprising as they comprise the contents of her compost pile, slowly breaking down

to become fertilizer for the garden.

Macko's mesmerizing photographs turn on the distinction between garbage and

compost. The dictionary offers two meanings of the former: garbage is 1) "wasted or

spoiled food and other refuse, as from a kitchen or household" and 2) "a thing that is

considered worthless or meaningless." Compost, by contrast, is defined as "decayed

organic material used as a plant fertilizer."

Far from being worthless, compost is an essential component of healthy soil and

hence of life itself.

Without the continual progression of decay and decomposition to new growth, there

would be no food, and thus no organic life on earth.

Momentarily arresting this process with her camera, Macko presents a vision of

time and life that is cyclical and fluid.

Despite their similar motifs and superficial resemblance, her photographs could not

be further from the western tradition of the Vanitas - those hyper realistic still life's

painted by Dutch artists in the 16 th and 17 th century to allegorize human mortality. In

such paintings details like rotting fruit, wilted flowers, lemon peels and extinguished

candles become foretastes of our own inevitable deaths. They posit our return to the

earth as a dread event that will be accompanied by Judgment and consignment of

the soul to the realms of heaven or hell. By contrast, Macko presents death and

decomposition, not as an end, but merely as a change of state. And she refused to

privilege growth over decay. Instead, her photographs document decomposition's

visual allure. As poet Wallace Stevens suggested in Sunday Morning, his meditation

on religion and mortality, "Death is the mother of beauty."

Macko shares this sensibility with other artists. One thinks in particular of the

photographs taken by Sally Mann at the Body Farm in Tennessee. The Body Farm is

a research facility where forensic students can study the changes in human corpses

left to decompose in natural settings. Mann used this site to create haunting black

and white photographs of bodies slowly being absorbed by the earth. As in Macko's

work it is the in-betweenness of the forms that make them so arresting -

recognizable parts of human anatomy blend into leaves, soil and underbrush. And

like Macko's the images are undeniably beautiful.

Macko's celebration of decomposition is part of a larger interest in erasing the

boundaries between humans and other parts of nature. She has for many years

worked with bees, creating multimedia works that draw connections between the

social structure of bee colonies and the lost histories of matriarchal cultures. Such

works grow out of Macko's feminist convictions. Her desire to mix categories, erase

borders and celebrate fluidity are in keeping with the ideas of various pioneering

feminist writers. One such is science historian Caroline Merchant whose 1980 book

The Death of Nature was one of the founding documents of eco-feminism. Merchant

took issue with Western culture's paradigm of dominion and conquest as it pertains

both to women and to the natural world. Looking back to a pre-industrial past, she

called for a radical reordering of human priorities. She hoped to replace the

mechanistic and patriarchal approach to society and the natural world put in place

by the Scientific Revolution with a more collectivist, female inspired model informed

by earlier organic conceptions of nature and society.

Ecofeminism discerns and fosters interconnections between society, nature, and the

cosmos. Because composting involves the recognition that life and non-life are

engaged in a continual process of exchange and transformation, it provides the

perfect metaphor for a new paradigm for social organization. Compost refuses to set

one state or one life form over another. Instead it displaces humans from their

privileged place from the top of the food chain. Shakespeare's Hamlet offers a wry

commentary on this reality following his inadvertent murder of Polonius. Noting

that all men are ultimately maggot food, the troubled prince tells his uncle Claudius

"A man may fish with the worm that hath eat of a king, and eat of the fish that hath

fed of that worm."

So it shouldn't be surprising that compost serves as an important theme in Donna

Haraway's most recent book. This feminist philosopher has long been engaged in an

investigation of the blurred boundaries between such supposedly antithetical

categories as nature and technology, humans and machines and individuals and

society. In Staying with the Trouble, she examines the possibility of a multi-species

world that she believes must succeed the current human-centric one that threatens

to bring all life as we know it to an end. The last chapter of the book presents an

allegorical story titled "The Camille Story, Children of Compost." It imagines five

generations of Camilles - hybrid humans who take on the characteristics of

endangered Monarch butterflies so that the species might survive together.

Compost here is shorthand for the intermingling of species, ideas and states of

being. Macko cites this text as an important inspiration. Considering compost from a

philosophical viewpoint, one can see why her photographs are so compelling. They

challenge our expectations of clarity and completion. Using photography, a medium

that historically has been considered an instrument of objective truth, Macko

presents compositions that exist in a delicious state of indeterminacy. Her

photographs take on the gestural expressiveness of paintings. Bits of food waste

create sensuous compositions as they are captured halfway in their passage from

solid to liquid. It is not surprising that many of the works suggest the creations of

artists who have also gloried in hybrid states. There seems a bit of Bosch in the

gaping red skin of a pomegranate in Wound, while in After Pollock, bits of vegetable

peels and skins scatter across the surface of compost bin like skeins of paint thrown

about in one of the Abstract Expressionist's over-all compositions. Often the titles

themselves underscore the intermingling of states. In Odalisque a cabbage becomes

a reclining nude, its green tinted skin as sensuous as any Titian. Bite features the

seeds of a yellow pepper clustering like threatening teeth beneath the smooth skin

of a leaf of romaine lettuce. The Light in the Creek is a radiant landscape dominated

by a fennel stalk whose tendrils suggest branches swaying in an underwater breeze.

Garlicwings Nebula is simultaneously cosmic and intimate as a translucent garlic

skin flutters like the wings of a celestial being.

There are fascinating literary references as well. In Dickinson, the pale bulb of a

decaying scallion suggests a white rose, a fitting emblem for the death-obsessed

poet Emily Dickinson. Similarly, in Miss Havisham's Desk the decay of nearly

unrecognizable stalks and leaves mimes the process of disintegration endured by

Charles Dickens' jilted bride as she waits for years in her wedding gown beside her

moldering wedding cake. In other photographs, tomatoes become clouds, onions

become eels and asparagus stalks suggest kindling for a pale green fire.

Macko notes that she has come to think about her compost photographs in terms

suggested by Michel Foucault's notion of heterotopia, his alternative to the unitary

fantasy of utopia. Heterotopias sow disorder, disrupting ordinary habits of thought

and forcing us to re-evaluate our assumptions about reality. As Walter Russell Mead

explains, "Utopia is a place where everything is good; dystopia is a place where

everything is bad; heterotopia is where things are different - that is, a collection

whose members have few or no intelligible connections with one another."

As heterotopias, Macko's photographs operate on multiple levels. Decompositions,

the series title, describes the process by which vegetable matter breaks down to

make its nutrients available for other life forms. But the term also suggests how this

work unsettles categories, taking them apart so that something new can emerge in

their place. As both metaphor and reality, compost represents the principle of

change and transformation. At a moment when it is too easy to imagine society,

nature and culture careening toward an irrevocable and inevitable end, compost

offers a message of hope. In this dark time, it is a promise of rebirth, an invitation to

imaginative freedom and a charge to align ourselves with the forces of change.

VISIT THE VIRTUAL GALLERY EXHIBTION HERE